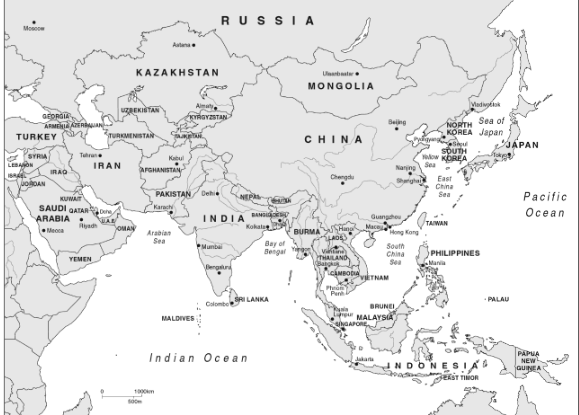

Epidemics have played a critical role in shaping modern Asia. In the book “Epidemics in Modern Asia. New Approaches to Asian History”, Robert Peckham, encompassing two centuries of Asian history, explores the profound impact that infectious disease has had on societies across the region: from India to China and the Russian Far East. The book tracks the links between biology, history, and geopolitics, highlighting infectious disease’s interdependencies with empire, modernization, revolution, nationalism, migration, and transnational patterns of trade. By examining the history of Asia through the lens of epidemics, Peckham vividly illustrates how society’s material conditions are entangled with social and political processes, offering an entirely fresh perspective on Asia’s transformation.

Since it is so relevant for the present time, we present here a summary of the chapters of that book.

Preface

There is, perhaps, no better place to begin a history of the global than with the hyper-local: the view over Victoria Harbour towards Tai Mo Shan, Hong Kong’s highest summit, from my office at the University of Hong Kong. Across the water to the north, Stonecutters Island juts out of the Kowloon peninsula. Acquired by the British from the Qing dynasty in 1860, along with Kowloon, Stonecutters Island has served over the years as a quarry, a military depot, the site of a prison, a smallpox hospital, and a quarantine station. As a result of land reclamation in the 1990s, it was joined to the mainland and today houses a large sewage treatment facility with a naval base operated by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Many Hongkongers are likely to be unaware of the history of Stonecutters Island, just as they may be unfamiliar with the history of Taipingshan, in Hong Kong’s Central and Western District, where an epidemic of bubonic plague broke out in 1894, often taken to mark the onset of the third plague pandemic. From southern China and Hong Kong, plague diffused along shipping routes to India, Australia, South Africa, North America, and Europe. Perhaps as many as 15 million people died worldwide. Today, hard-surface ball courts and a small public garden mark the spot where, following the Taipingshan Resumption Ordinance in September 1894, the British demolished the crowded Chinese tenements at the epicenter of the outbreak.

The contemporary landscape of Hong Kong, like many other Asian cities, has been shaped by disease episodes of the past. Yet most accounts of the transformations that have taken place across the region over the last few centuries focus exclusively on political, social, economic, and cultural upheavals. For the most part, disease is mentioned only as a backdrop to more momentous events, relegated to a footnote, or overlooked altogether. The aim of this book is to write epidemics back into history, examining the transformative role that disease has played in making modern Asia, and suggesting how the threat of infection continues to influence societies across the region today.

Epidemics in Modern Asia proposes a new transnational approach to modern Asian history and global modernity; one that places emphasis on connections and continuities over space and across time – as well as on discontinuities – and, in so doing, resituates the experience of epidemics at the heart of Asian history.

Contagious histories

Throughout 2014, an epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa dominated the global media. While the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the epidemic a public health emergency, images of makeshift quarantines, field-laboratories, and bagged bodies fueled panic in many countries around the world. The high mortality rate of up to 90 percent, together with graphic details of the symptoms, which may include internal and external bleeding, added to public concerns. In Hong Kong, health authorities stepped up surveillance and rushed to implement Ebola contingency plans. Travelers from West Africa who showed symptoms of fever were quarantined and tested. Authorities in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), conscious of the large numbers of Chinese workers in Africa, heightened border controls.

Two other viral infections also caused alarm across Asia. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), a highly pathogenic viral illness, was first reported in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Arabian economy is dependent on some nine million non-national residents, many of them migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia. Every year millions of pilgrims from across Asia converge on Saudi Arabia for the hajj, the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca. In May 2015, an outbreak of MERS in South Korea led to the imposition of quarantine measures, the closing of schools, and – amidst public panic – the establishment of specialist MERS clinics in major cities. By mid July 2015, there had been 186 confirmed cases of infection with 36 deaths.

Meanwhile, in March 2013, human cases of the novel avian influenza virus H7N9 were reported in China. A WHO announcement about the new virus, which was posted on Twitter, prompted up to 500 retweets per hour. By December 2013, there had been 143 laboratory-confirmed human cases of H7N9 with 45 deaths. A 36-year-old Indonesian domestic helper, who had visited a live poultry market and slaughtered a chicken across the border in Shenzhen, became the first confirmed H7N9 patient in Hong Kong. This sparked a ban on poultry imports from Shenzhen farms and a heightened alert in hospitals.

1 – Mobility

In the nineteenth century, concerns about intensifying interregional and global mobility prompted impassioned debates in many countries about where, how, and by whom the boundaries were to be drawn that demarcated the individual from the state, the nation from the world. This chapter examines these debates in a number of sites across Asia, specifically in the context of epidemics and the entanglement of different kinds of circulation that they brought into view: the traffic of disease, the transference of people, goods, and capital, and the dissemination of knowledge and technical expertise. In what ways did epidemics foreground economic and social networks? How were different species of mobility encouraged, regulated, or prevented? What kinds of violence did epidemics induce, particularly in relation to conflicts over freedom, power, and sovereignty?

It is, perhaps, too easy to think of mobility solely in relation to trade, migration, and the spread of disease – in other words, as an outward diffusion or expansion that impacts upon a more-or-less static ‘target’ society. According to this view, mobility is conceived as an exceptional process, in contrast to the fixed locations from which – and to which – the person or thing is moving. Mobility has tended to be understood ‘through the same analytical lens’ of global flows, with the mobile contrasted to the static. It has also been associated with the transition from a world where modernizing institutions were able to fix identities and relations, to one that is increasingly mobile and therefore hard to order. The argument has been made that global capitalism, coupled with new information technologies, has produced an unsettling new fluidity: ‘liquid modernity.’ Modern life is characterized by a fundamental inconstancy – by ‘fragility, temporariness, vulnerability and inclination to constant change.’

Studying epidemic episodes in the past may help us to rethink this binary between mobility and fixity, localization and transnational connection, past and present. As the anthropologist James Clifford has suggested, we might begin to re-conceptualize mobility by reflecting on the processes of human movement or travel inherent in culture. ‘Practices of displacement,’ Clifford proposes, may be thought of ‘as constitutive of cultural meanings rather than as their simple transfer or extension.’ In each of the three cases presented in this chapter, I elaborate on this insight by exploring epidemics in relation to different kinds and scales of mobility.

2 – Cities

How has urbanization influenced the diffusion of disease? To what extent have epidemics shaped urban space and determined how cities are experienced? This chapter addresses these interrelated questions by considering epidemics in relation to a number of cities. Each of the four cities considered here – Batavia, Hanoi, Singapore, and Bombay – are colonial cities, in as much as their development took place within the context of colonization. The term ‘colonial city,’ however, is problematic, ‘blurring as many features of the reality as it illuminates.’ What is a colonial city? Most cities in history might in some sense be viewed as colonial in that they have subordinated their agrarian hinterlands in a manner analogous with a colonizing power. ‘The local relationship of town-to-country,’ Anthony King has noted, ‘becomes the metropolis–colony connection on a world scale.’ At the same time, municipal authorities in the second half of the nineteenth century mobilized many of the same instruments in order to regulate the behavior of native city dwellers at home and abroad. To this extent, at least, ‘Bombay and Manchester were “colonized” in the same way.’

The aim in this chapter is to chart different epidemic histories through the biographies of Asian cities from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century in order to illuminate facets of the interrelationship between epidemic disease and urbanization. As a process, urbanization may be defined as the spatial concentration of a population that results from the centralization of government and the clustering of economic activity. In the previous discussion, we considered the port cities of Manila, Nagasaki, and Hong Kong as contact zones: sites of epidemics where different scales of mobility converged, generating friction and violence. In this chapter, I develop these ideas to show how epidemics both propelled and stymied urban growth, even as cities produced different kinds of epidemic threats. In a European context, the historian Richard Evans has explored the inner life of Hamburg in relation to cholera epidemics – and in particular the epidemic of 1892 – demonstrating how disease highlighted social inequalities, shaped the city’s municipal politics, and above all created the conditions for political reform. Similarly, each of the four case studies in this chapter considers specific aspects and moments in the history of a city to shed light on the management of urban space and infectious disease.

3 – Environment

Natural disasters, such as hurricanes and tsunamis, have long been viewed as the result of external biophysical forces acting upon human societies. They have been understood, in other words, as implacable natural processes beyond human control. More recently, particularly as a result of concerns about global climate change, there has been a shift of emphasis onto the anthropogenic causes of such adverse events. By destroying features of the environment, such as mangroves and wetlands, that provide protection from storm surges, humans are amplifying the effects of these extreme occurrences. While earlier histories tended to minimize the role of the social in natural disasters, more recent approaches have stressed the part played by human agency. Human history is increasingly viewed within an ecological framework. Expressed somewhat differently, we might say that the emphasis on human-made determinants of natural disasters reflects a deeper notion that people are ‘inescapably part of a larger ecosystem.’

Epidemics share many characteristics with natural disasters. They are the result of identifiable natural processes that lead to loss of human life and damage to property, infrastructure, and business; their impact may be mitigated by a population’s preparedness; and above all, of course, they require susceptible populations. Disease outbreaks – or fear of them – are often a by-product of other species of disaster. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which killed an estimated 280,000 people across South and Southeast Asia, with a million displaced into temporary camps, gave rise to concerns about epidemics of water-borne and food-borne infectious diseases, such as salmonellosis, typhoid fever, cholera, hepatitis, and shigellosis. By and large, these fears were not realized, but the specter of epidemics nonetheless shaped emergency responses to the tsunami. In this chapter, I probe the role of human agency in disease emergence and consider epidemics as episodes that foreground the convergence of human and natural ecologies. To what extent should epidemics be understood as the outcome of environmental crises? What countervailing effects have been produced by attempts to intervene with the environment to mitigate disease threats? How have evolving conceptions of disease shaped environmental change? And, finally, what role does politics play in determining human–environment relations?

As we saw in the previous chapter, cities have been important catalysts in Asia’s environmental transformation, drawing in migrants to work in expanding industry.

4 – War

War and infectious disease are often viewed as ‘fatal partners.’ On the face of it, the connection between conflict and disease appears self-evident. Conflicts amplify disease risks by creating conditions conducive for disease to spread; as military personnel move and as non-combatant populations get displaced, the likelihood of epidemic outbreaks increases. The destruction of infrastructure and disruption to services, including vector control, may produce environments where diseases are more likely to take hold. It has been argued that dengue fever became hyper-endemic in regions of Southeast Asia during and in the aftermath of the Second World War, not only due to the spread of genus Aedes mosquitoes (notably Aedes aegypti), which are vectors of the dengue virus, but as a result of urbanization and environmental degradation, which created mosquito breeding grounds. Epidemics of dengue hemorrhagic fever were consequences of this changing ecology. Wars have also been crucial in the spread of plague (Chapter 1). Defoliation in southern Vietnam as a result of US herbicide spray missions to destroy agricultural land and forest cover in enemy held territory during the Vietnam War (1964–1975), coupled with the collapse of local infrastructure, are thought to have led to increased contact between humans and wild (so-called ‘sylvatic’) sources of the disease.

War has also been a spur to migration. Those displaced may lack acquired immunity to diseases that are endemic in the areas they move to (Chapter 3), and they may introduce new diseases. Migrants may be physically and emotionally traumatized, and war may produce food insecurity and malnutrition. In crowded refugee camps, the interplay of all these factors may lead to epidemics. Often different diseases are intertwined and their co-emergence and co-transmission are associated with specific socio-political conditions: for example, discrimination, poverty, and violence. The term ‘syndemic’ has been used to describe the interaction of two or more co-existent diseases, as well as the social and economic inequities that drive them.

Some historians, however, have taken a more skeptical view of this straightforward correlation between war and epidemics, calling attention to changing ideas about war epidemics over time. The war–epidemic relationship is often treated as self-explanatory and has become so entrenched and taken for granted that there has been relatively little critical attention paid to the dynamics of their co-evolution.

5 – Globalization

From the 1930s, Asia was at the forefront of an international push for development. Across the region, there was an emphasis on tackling infectious diseases, particularly in the period after the Second World War, which witnessed anti-colonial struggles in many Asian countries and the rise of ambitious global programs of disease prevention. In April 1948, the Health Organization of the League of Nations was transformed into the WHO, reflecting an optimism about the prospect of controlling infectious diseases by deploying the tools of modern biomedicine and public health, especially antibiotics, vaccines, and drugs, as well as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), an insecticide widely used to combat malaria. Eradication – the ‘reduction of the wo

rldwide incidence of a disease to zero as a result of deliberate efforts’ – became the avowed goal of international health organizations and national governments. In 1972, the virologist and Nobel laureate Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet (1899–1985) posed the question, ‘On the basis of what has happened in the last thirty years, can we forecast any likely developments for the 1970s?’ To which he answered: ‘If for the present we retain a basic optimism and assume no major catastrophes occur and that any wars are kept at the “brush fire” level, the most likely forecast about the future of infectious disease is that it will be very dull.’

Post-Second World War optimism was embodied in the Declaration of Alma-Ata, the outcome of an international conference convened in September 1978 in Kazakhstan. In the Declaration, WHO member-states along with numerous international organizations affirmed the UN’s definition of health as a ‘fundamental human right’ and launched a global campaign of ‘Health for All by the Year 2000.’ As the science journalist Laurie Garrett has observed, ‘The goal was nothing less than pushing humanity through what was termed the “health transition,” leaving the age of infectious disease permanently behind.’

There was political significance in the decision to hold the conference in Kazakhstan, a Central Asian country with a common border with China, which was then part of the Soviet Union. Given global health disparities, the WHO had studied a number of developing countries that had successfully implemented local-level health campaigns. In particular, China’s national ‘barefoot doctors’ policy from the late 1960s influenced WHO’s global Health for All program.

Conclusion: Epidemics and the end of history

Until recently, and with a few notable exceptions, social and political histories of Asia had surprisingly little to say about disease. Despite the historical impact of epidemics on human societies in terms of mortality and morbidity, there has been a reluctance to invest such episodes with the significance attached to a war or a dynastic change. Epidemics take center stage only when they cannot be avoided, and even then they are most often invoked as contextual material for narratives that hinge on social, political, and economic developments. This has led to a striking asymmetry: while pages in textbooks on China are devoted to the collapse of the Ming dynasty in the 1640s, only a few sentences are included in passing on the loss of life that resulted from catastrophic epidemics. Similarly, while tomes are written about the First World War, comparatively little attention is paid to the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic in India, which may have killed up to 20 million people – far more than the sum total of those who perished in combat.

One reason for this relegation of epidemics in history has been that they have tended to be viewed as exceptional occurrences. They have been construed as exogenous events, extrinsic to the societies they affect. Like natural disasters, epidemics are understood to crash into communities from without: they belong, accordingly, to a space outside human history. Another reason is that examining the history of infectious disease is deemed to require specialized knowledge and expertise that goes beyond textual scrutiny of the historical archive. How can we write about infections if we have no formal training in, say, epidemiology or microbiology? Because epidemics are intertwined with environmental issues that are vast and complex, they are difficult to grapple with. To engage with such issues and the incommensurable scales they comprise (the very focused and the expansive), history would need to become radically transdisciplinary. It would also involve uncertainty since many questions about the origin and identity of diseases in history cannot be readily answered. William McNeill has expressed this tension succinctly: ‘We all want human experience to make sense, and historians cater to this universal demand by emphasizing elements in the past that are calculable, definable, and, often, controllable as well’. Epidemic disease, when it did become decisive in peace or in war, ran counter to the effort to make the past intelligible.

From:

Peckham, R. (2016). Preface. In R. Peckham (Author), Epidemics in Modern Asia (New Approaches to Asian History, pp. Xiii-Xviii). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316026939.001

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/epidemics-in-modern-asia/7ED46DD207C9484B906535DE414D04AF

Pubblicazione gratuita di libera circolazione. Gli Autori non sono soggetti a compensi per le loro opere. Se per errore qualche testo o immagine fosse pubblicato in via inappropriata chiediamo agli Autori di segnalarci il fatto e provvederemo alla sua cancellazione dal sito